2021-10: Santa Rosa Circuit

- Jan 28, 2022

- 15 min read

After the unexpected stay at Santa Cruz and the miserable crossing that had preceded it, the remaining leg to Santa Rosa was a cakewalk. I dashed off the boat as soon as we made contact at about 2:30 pm, with no gear from below to retrieve, and headed straight for the southeast corner of the island. I stopped at the Water Creek Campground to fill up about 6L-- it was the only guaranteed water until sometime the next morning, depending on my appetite for night hiking and my pace. Smoke from the mainland fires swept in as a haze, though later it would draw out the colors of sunset for hours. I stopped by the grove of torrey pines-- one of only two in the world, each with their own distinct subspecies, and marveled in the sight. Somehow, for some reason, this lonely grove was the last remaining trace of a species that had blanketed the western US during the ice age. And now I'm here, walking around, with the grey skies of the end times overhead. It's a bizarre feeling.

Torrey pines overlooking the road below

The trail is flat, a fire road following the coast east. Barring the trip up to the pines, and a canyon or two, it made for incredibly fast travel. Even with the Kumo a bit past its max carry, I still found myself jogging in sections. But any distance I traveled efficiently was offset by my inability to stop taking pictures. The island is dry, sure, but there's life all around, and the sheer scale of it is hard to get past. With Santa Cruz in the distance and the mainland behind it, with the waves crashing against the beaches and bluffs, and with the trail sometimes visible for miles ahead, the open and dramatic landscape leaves a marked impression.

North coast beaches, open roads, Santa Cruz beyond

The trail veers inland to bypass Skunk Point and the protected bird sanctuaries, though I'd like to go back-- it's apparently a massive sandy beach of blown dunes, beach scrub brush, and a panoramic view of the ocean. I found myself passing by the first of many abandoned ranch buildings-- while the buildings on Santa Cruz are restored and historic, the ranches on Santa Rosa have returned to the elements. In some places, all that remains are corrugated iron roofing or fencing. In others, wooden sheds are completing their decay. I rounded a bend toward East Point and was immediately enamored with it-- the birds circled overhead and there were tide pools scattered among the shore, unreachable between the steep, slippery rocks and the waves. Here, the island was no longer sheltered from the sea by Santa Cruz, and the waves were wild and driven hard against the rocks, their cadence unpredictable as the swells came from all sides. Great rafts of kelp appeared and disappeared with the rolling horizon, and the birds began to flock home as the sun set knife-edge with the coastal bluffs.

The tide pools, covered by the break

The wind had intensified as I'd traced the coast, but picked up, as the day before, as sunset drew nearer. With no shelter in sight, and it seeming unlikely I would make it all the way to San Augustin beach, I took a use trail up the bluffs, looking for any kind of protection. This is where research helps: I'd made sure on google earth that this particular use trail connected with the main road after a few miles; I didn't want a repeat of the dying-of-thirst-in-Big-Sur situation. And the selection was good, this particular use trail is stunning, winding along the edge of the bluffs, as they rise out of the ocean, bounding along the crest of the hills before joining back up with the slightly more restrained, slightly more inland Sierra Pablo road. The road quickly bags Sierra Pablo peak (1144'), but by the time I had reached it, the light was fading quickly. I had misjudged how fast the night would come, unused to October, and I was desperate for shelter from the wind. As time wore on, with nothing suitable, I began to worry I wouldn't find a spot flat enough for my tent. I tried shoving myself into some bushes, but they provided no protection from the wind, and I kept on. My desperation increased, and I ran along the trail, looking for anything.

Finally, on an exposed saddle high above the sea, I found a sandy flat spot directly in the middle of the trail. Losing light, I struggled to get my tent up in the wind. Left unattended for a moment, it would be lifted up, gone. Even with my pack, water, and entire collection of current earthly possessions on one end, it flapped violently while I staked the other end, sitting on it to keep it down-- though only barely. I pivoted to the other side, extremely grateful for the 12" blizzard/sand stakes I had brought instead of my usual 4" ones. The tent was up. It was an ugly, ugly pitch, but I crawled inside to try to cook some dinner. It was only cross-legged, with my stove between my legs, that I was able to get the gas to catch with the wind tearing through the mesh. The air currents were visible in the last glow of the day, as the smoke traced out their patterns, rising and falling over the crest of the island.

Smoke patterns in the wind from the Sierra Pablo crest

30 minutes after the first appreciable darkening of the sunset, it was pitch black, and the wind found another level of severity. Despite my stakes, I spent much of the night listening for gusts, and then reaching over my head to brace the main pole of the tent-- if I didn't, it would be knocked over in an instant, bringing the whole thing down on my face. The few times I did sleep, a momentary reprieve from the screaming wind, the scattered sand, and the flapping of the tent walls, I awoke with the cold silnylon and accompanying trekking pole plummeting down toward me. At a certain point in the night, the foot-side pole collapsed, and it was well beyond my motivation to fix. The night and the sound was interminable. I lamented the lack of sleep, and I tossed, and turned in the darkness. And suddenly, I awoke, to the sun, and to stillness.

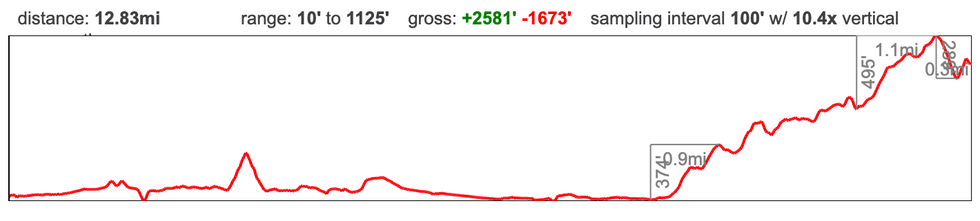

Stats for the (half) day:

12.8 mi (in 4.5 hr!)

+2600' / -1650'

I was beginning to understand that the wind was only quiet from around 5 am to 10 am, but I was also so sleep deprived that I hadn't taken advantage of this and had instead caught up on much-needed rest. The miles came extremely easily that morning, as I was nearly out of water, the path was flat and well-graded, and my spirits were high with the wind down.

I nearly immediately ran across Clapp Spring, a clean and clear trough with a cleaner and clearer trickle filling it from a pipe. The original plan had called for a massive filter here, up to 8L total, but the ranger had told me that there was reliable water at Wreck Canyon, a few miles down the trail from me. I filled up what I'd need for the next few hours, and the trail took a sharp turn down to the beach, bounding across the tops of the rolling hills. The climb out of Clapp wasn't anywhere near as bad as I'd expected, and between the sea below and the neat geology, I made good time.

Wreck arrived sooner than I had expected it to, and it was nothing like I had expected-- a bushwhack through cattails, soggy ground, flies, and no clear water source. I eventually found a mud puddle with some evidence of water flow, which is maybe one step up from cow water, maybe not, depending on who you ask. But after extensive searching, it was my only option, so I sat down in the bog and started filtering up to my max capacity.

The finest water money can buy! Straight from the source!

It's worth a quick aside to talk logistics. The Kumo is a wonderful pack, but not a very big one, and not one rated to haul a lot of weight-- 20lbs comfort, 25lbs max-- and I use it comfortably with an 8 - 10 lb baseweight. With 18 lbs of water, I likely brought the pack up to 33 lbs after food. Fitting the water was another story. I had my 2 clean 1.5L smartwaters in the side pockets, and the 1L dirty bottle and a 2L platypus in the outer mesh pocket. The final 2L platy was inside the pack itself, jammed horizontally, sitting nicely between my food and my tent. I prayed it wouldn't pop. This is to say that, while this was possible, and while I would do it again, it's important to think through this aspect of a trip while planning, especially if solo.

This is also to say that after Clapp, I was struggling. The weight, the sun, my complete lack of sunscreen or sun protection, the sunburns I'd already gotten, the weight, the weight, the weight-- it really all added up to make for slow going. At the very least, the scenery was gorgeous, massive, rugged, and the beaches were crowded with sea lions, the trails so full of foxes that I became desensitized to them, and the sky dotted with wheeling birds.

The south coast, looking west.

The foxes are relatively unafraid-- for wild animals

As overburdened as my pack was, even the slight undulations in the trail as it traversed the very lowest stretches of the canyons were difficult. With nearly no shade, it at times took genuine effort to enjoy the scenery. But despite the difficulty, the stretch of trail along the seaside passed more quickly than I realized, and before long, I was at an abandoned farm building at the foot of a long, long climb, one that would take me all the way up to one of the two peaks of Soledad, the highest points on the island. I took a much needed break in the shade, a rarity and one that was greatly appreciated after near-constant sun since I'd stepped out of my tent that morning. A good opportunity for lunch and to use a wag-bag-- while I ignored the rules on camping, confident in leave no trace, packing out waste is critically important on such a small and fragile ecosystem.

I felt relatively strong after a lengthy rest, and after making meaningful progress through my water, despite the 1700' climb to come. It looked exposed the whole way, but a gentle incline, graded once upon a time for vehicles. And despite the "easy" part of the day being behind me, and the "hard" part yet to come, I felt good, I felt ready. And so I set off, with the sea at my back, the wind in my face no matter which direction the road twisted and turned, and I made great time up the hill. The gentle grade at first seemed to be making very little progress at all on the substantial climb, but it's also easy enough on the legs that one can be surprised how quickly and with how little effort the trail has in fact ascended, once the primary focus is no longer on the worthiness of each step. I took a short detour toward the lighthouse at South Point, but was deterred by the low amount of daylight remaining with respect to the distance I intended to cover.

The winding road visible below

The climb that I had dreaded was nearly over before I knew it, with my first views of the island's rugged west coast peeking through. The west is remote, stark, impossible to access without picking a canyon and following it all the way down, a ten mile round trip. But if I return, I'd like to trace out the coastline, since it is a single continuous beach from the southernmost point up to the north edge of the west coast, ever so often broken up by a canyon or bluff, but seemingly navigable from end to end, and perhaps the least traveled section of the least traveled National Park.

And as I reached the highest ridge on the island, Soledad just across a sidewalk-in-the-sky, perhaps the most interesting section of the trip commenced. The fog began to roll in. By the time I had tagged the high point and continued northwest, the rolling ridgeline was partially obscured, and the broad northern plains that had been so visible only ten minutes before seemed to have never existed. The fog hit me with a visceral force, with the cold and wet of the ocean, and I threw on my rain jacket to keep the damp out.

Ridge trail with the plains below all but invisible

The fog thickened, moving impossibly quickly, washing over the ridges and hills of the island, the wind trying to push me over as well. At poorly-signed or unmapped junctions, I had to rely on GPS to verify which route was correct-- the visibility moving forward was too poor to be certain. I reached the final high point of the section, the last great rise on the highest ridge, and as I set downward, the fog grew thicker and thicker. I worried it would only get worse, and that setting up camp would be a miserable endeavor.

And then suddenly, the fog cleared. I stumbled out of it as though through a door, as though I had broken through a wall. I exited the fog into a small bowl, a little circular valley, and thought at first that I had simply escaped from the wind, that the moment I crested the next hill I'd be right back in it. But instead, at the top of the next rise, the plains were visible again, and the fog and the smoke cast the colors of sunset over everything; the relatively drab colors of chaparral became a brilliant orange.

Slideshow: sunset colors on the second day

The view was incredible, and it remains in my mind as perhaps the highlight of the trip. And while the smoke and fog may have drawn out the sunset, it did not delay the darkness. The wind was picking up fiercely, and I knew I would, again, not make it to a legal camping site at a beach. I tore down the trail, the fog rolled in thickly, the light began to fade, and the wind became its now-familiar terrible self. I looked for shelter anywhere, but the wide plains were nearly featureless. I pulled out my headlamp and committed to some night hiking, but after nearly half an hour, the best I had found was a stand of brush maybe waist-high. I hoped it would help, and I set about getting the tent up. But the ground here was too loose to hold a stake in some places, and rock-hard in others. I put together a makeshift pitch, but several of the stakes were tenuous at best, and I would spend the night crawling out of my tent to re-pitch. It was not my best night of sleep, but at some point, it was morning.

Stats for the day:

20.7 mi

+4250' / - 4650'

In retrospect, Santa Rosa provided some of the worst sleep I have ever gotten on a backpacking trip, second to the time my tent was circled by a screaming mountain lion all night. This morning, though, was the worst of my island sleeps. My tent and sleeping bag were soaked with dew, I discovered a massive spider next to my face-- which frankly, didn't need to be there-- and upon exiting my tent to begin drying my gear, as immediately swarmed with biting black flies.

I put in my contacts, brushed my teeth, ate breakfast, re-allocated water, and packed my bag while pacing a 100-foot stretch of trail to make it a little harder for the flies. I was exhausted before I even put on my pack. But my water reserves were low, my pack was light, and when I finally hit the trail, I was in store for the easiest walking of the trip. The northern plains are flat, unmarred except for the creek valleys running through it. The fox sighting were numerous, and I quickly crossed Cañada Verde, which was another fox-tail bog like Wreck, though without apparent water.

The walking was easy, if the views were a bit dry. But this fella posed!

I met the only person I'd see in the backcountry, and we quickly exchanged beta before continuing our separate ways. I was feeling strong and was a bit ahead of schedule, and I really wanted to head down Cow Canyon to reach Cow Beach, but looking at the dry creekbed, wasn't sure if it would go-- or if it would, if it would be any faster than simply heading down Lobo and traversing the coastline. I steered down Lobo and reveled in the sights. The trail was relatively slow going here, with low trees, stepping stones through water, and some brush, but the views were phenomenal.

The high point, though, was reaching the ocean and traversing to Cow Beach. Lobo is phenomenal, and is a worthy dayhike for anyone camping at Water Canyon-- the geology is thrilling, and it's by far the greenest section of the island, the most abundant. But the coast is so wild, so rugged, so alive, and the traversal is so thrilling, that I would recommend it to anyone already heading down Lobo. The force of the waves slamming against the bluffs, sending the spray up into the air, the sound, the feeling of it, can't meaningfully be conveyed.

Reaching Cow Beach was its own reward, too. The waves still rolled in heavy, but the beach was relatively tranquil. Completely isolated, it felt like I was in a totally different world than the obviously-trafficked Lobo. Not visible in the view below is a significant cliff that nearly prevents access to the beach. There was a plausible way, but not one I wanted to take solo. Slick sandstone isn't a fun chance to take alone. There was, however, a perfect trickle of water, a tiny waterfall dripping onto the sand-- I took the opportunity to filter up for the rest of the day, and spent a good amount of time here.

Made it with maybe a quarter of a liter to spare!

In a perfect world, I would've descended Cow Canyon and reached Cow beach directly, then ascended Lobo-- but Cow and its alternatives looked to be overgrown and slow going, at best picking my way down a rugged dry creek, at worst, fighting through tick-likely brush. The less elegant but significantly simpler route saved from the uncertainty, but knowing what I know now-- namely that there was water at Cow-- I would've pushed down the dry creek, not needing to hold Water Canyon as a backup. However, Lobo is scenic enough that I didn't mind passing through twice. At noon, none of my photos captured Lobo with any manner of justice, and as it's reasonably accessible from the pier, and thus subject to some stellar photography, anyone curious as to how it looks can easily find answers. I can just affirm that it is worth visiting!

An unnamed wash looking toward the completion of the loop at Water.

The traversal across the beach and back up to the ring road was beautiful, but I started to hit a mental wall. While I wanted to complete my loop by swinging out toward Carrington Point, I was more interested in using a real restroom at the campground rather than another wag bag, and could feasibly complete the section in the morning. I elected to head back toward the campground directly from Lobo, and made good time doing so. I arrived at camp much earlier than other days, around 2 pm, and had a pleasant several hours journaling, watching foxes and ravens torment a few guests, and chatting with some of the friends I had made. I set up camp and cooked dinner in the shelter of a wooden wind break, and the air in the sheltered canyon was cool and still.

I tossed around a few ideas for the following morning-- I could summit Black Mountain and exit the loop nearly at Lobo, then tack on Carrington for some heavy mileage. But, not knowing exactly what time the ferry would arrive, and not having more than maybe 2 spare meals, I didn't want to miss the boat and sign up for 2 more days on the island. I could take a relatively uninspired Black Mountain - Ranger Station - Carrington Loop, but that seemed too easy. I settled on a happy medium: an intermediate loop just involving a tiny bit of cross-country to connect Black Mountain to a branch off the ring road. This was, as with most of my ideas, poorly thought out. But that's a tomorrow problem.

Stats for the day:

17 mi

+2800' / -3200'

I got a late start, between finally getting some good sleep, having a deeply relaxing morning chatting with a few folks, and doing some yoga to save my legs. By the time I made it to Black Mountain, I had only a few hours before the earliest side of the ferry window. I spent some time scrambling around the hillside, looking for the right ridge to take me down to the intended road-- I never found it. Looking on google earth, I can see no trace of the trail-- since it's a dead-end, I don't imagine it gets much use, and has likely been reclaimed by the foliage. Having wasted a good amount of time and energy, I took the shorter route down to the docks. Although I could've pushed on and completed Carrington, I didn't want to-- instead, I took off my pack, walked in the water, looked at some birds, chatted with some friends, played some guitar, and unwound from a relatively intense trip. I had covered a lot of ground, and overcome numerous unexpected challenges. I had legally camped 0 times, hiked exactly 69 miles, pushed my pack well beyond its weight rating, slept far too little, and survived a tortuous ferry ride. But even in the moment, I was able to look back with fondness on the experience.

Stats for the day:

8.5 mi

+ 1900' / -2000'

The ferry came several hours later, on the latest side of the arrival window. I didn't mind. On the way back we toured some sea caves, came across a massive pod of pacific white-sided dolphins, saw a handful of whales, and, all of a sudden, were expected to re-enter civilization. Never before has my trailhead been 5 minutes from the 101. I sat in stunned silence in LA traffic, feeling as though I had been wrested from the island, as though I had left something behind, not entirely sure how to reconcile what I had just been experiencing with what I was now experiencing. It was jarring, confusing, odd. I don't know how to explain what I felt, but perhaps at the core of it was a deep gratitude to have been able to take the trip at all, and a dissonance of the experiences that I wanted from the ones I was currently taking in.

Something happened with my camera, it seems as though nearly all the pictures have been deleted-- I'm sure through my own fault. So what we have here, on this page, is what you and I both will remember this trip by. I think the route is promising, and a tempting alternative to the TCT for those looking for more isolation and solace. Let me know if you give it a shot!

Comments